The Rise of Kamikaze: Why Japan Turned to Suicide Attacks in WWII

- Paul D. Wilke

- Sep 30, 2024

- 29 min read

Updated: Feb 12

The Cult of Disposable Heroes is Born

On 15 October 1944, the base commander of Japan's 26th Air Fleet in the Philippines, Rear Admiral Masafumi Arima, solemnly removed his rank and insignia, climbed into a Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bomber, and departed on a mission to crash his plane into an American aircraft carrier. He told his men he didn't plan on returning and was true to his word.

And then...anticlimax.

Perhaps he took a shot at the carrier USS Franklin. Or not. Nobody knows for sure what happened to the brave Admiral. We only know he never returned and no ships were damaged or sunk on that day. None of this mattered to Japan's state-run media, which seized on his death and transformed it into a more cinematic news story. This new and improved version had Arima going out like a sky samurai after slamming into an aircraft carrier and sinking it.

Of course, this wasn't true, but who cares? Mythologizing Arima served a larger purpose. The Japanese needed inspiration and hope. And more than anything, they needed a hero. By the autumn of 1944, even the most delusional nationalists understood how badly Japan was losing.

And so Arima's death got repackaged through the media's mind-warping propaganda machine and fed back to the public to shift the narrative away from that creeping sense of doom everyone felt. It offered the dangerous illusion that there still might be a winning strategy if only enough men like him volunteered to make the ultimate sacrifice. If only.

Indeed, the propagandists proclaimed, here was an example to follow!

Think about it: One man, one honorable man, one brave and honorable man filled with selfless patriotic fervor who gave his life for the nation and took out an enemy aircraft carrier. One man can move mountains...or sink ships. A death like this resonated in a society that still honored the Bushido ("way of the warrior") ethos of the samurai, in which duty and honor meant more than preserving one's life.

Not to nitpick, but Arima wasn't the first kamikaze - others had been haphazardly crashing into ships for some time. But those were spur-of-the-moment decisions taken in the heat of battle, not anything consciously decided upon before climbing into the cockpit.

There had been talk at the highest levels of adopting suicide tactics as a part of an official strategy, though nothing had come of it. Such a move was considered too drastic in the war's first years. That was about to change.

A few days after Arima's flight into legend, Vice Admiral Takijiro Onishi, the new base commander, used his predecessor's death as the inspiration to organize a "Special Attack Corps" devoted to suicide operations. Onishi, a pioneer of Japan's naval aviation and one of the planners of the Pearl Harbor attack, had been a long-time skeptic of so-called "body-slamming" tactics.

Not anymore. He would go down in history as the "father of kamikaze." Over the next nine months until the surrender, his kamikazes would inflict more damage on the U.S. Navy (USN) than the rest of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) did during the entire war. Still, it wouldn't be enough to prevent or slow down Japan's defeat.

Why did the Japanese resort to kamikaze?

To answer this question, I'll divide this essay into two parts: first, the historical background that explains Japan’s increasing desperation. The switch to kamikaze makes more sense once you see what they were up against.

And second, how Onishi's tactical innovations altered the dynamic of the Pacific War by giving his aviators a way to hit back at the Americans, a capability they had lost by late 1944 as they found themselves trapped in a vicious cycle that went something like this: Japan desperately needed frontline pilots to replace its losses, so corners were cut in training. Aviators went into combat far less prepared than their American counterparts, resulting in catastrophic losses that they couldn't afford to take. Now, repeat this cycle but now with worse training, and the predictable results were more lopsided battles.

Onishi realized this was only going to get worse once America stationed heavy bombers within range of Japan's home islands. Then, the already-stretched Japanese air force would need to be diverted to defend the skies over Japan.

He was right: that nightmare scenario was only months away. Add to this the fact that America produced far more planes, pilots, and warships, and far better ones than the Japanese could ever match, and you have a recipe for defeat.

Kamikaze tactics offered an innovative way to work within Japan's resource and production limitations while giving it a powerful weapon against the USN. If inexpensive and obsolete aircraft could hit and sink enemy warships, especially carriers, perhaps there was a way to inflict enough pain on the Americans to convince them to negotiate peace.

Maybe...but maybe not. That was the hope, anyway.

Japan! vs. America!

Onishi had just taken command of the First Air Fleet, putting him in charge of Japan's naval air forces in the Philippines, or what was left of them. This was probably the worst job in the Japanese military, which is saying something. When he arrived at the Mabalacat airfield near Manila on 15 October 1944, only 30 combat-ready aircraft remained.

The fierce aerial battles of the last few weeks had exacted a heavy toll. Around 1,000 planes had been lost. [1] Taking stock of the inventory at his disposal, Onishi realized that his remaining forces wouldn't be enough to stop an American juggernaut that appeared to have an endless supply of fighters and bombers.

How did it get this way?

By October 1944, no sane person believed Japan could win the war anymore. Two years of steady defeat and constant retreat had dispelled that notion. The battles of 1942 and 1943, at Coral Sea and Midway, and the long, grinding Solomon campaign, had chipped away at Japanese air and naval strength. Both sides took heavy losses, but America replaced what it lost and then some. Japan simply couldn't.

That should come as no surprise. Japan's industrial capacity was only about 10% of America's and lacked easy access to the natural resources needed to wage modern warfare. [2] For example, it depended on crude oil from the distant (and therefore vulnerable) East Indies.

Even more troubling, America, the nation Japan so foolishly picked a fight with, had been supplying 80% of its oil up to 1940. [3] A defensible and adequate alternative to that lost American oil was never found. That turned into a massive problem after the invasion of the Philippines in October 1944 cut the Japanese empire in two.

Historian Ian Toll described Japan's tenuous supply line as "a 3000-mile-long femoral artery. If this artery were severed, Tokyo's war-fighting economy would soon bleed out, and defeat would become inevitable." [4] Onishi understood that MacArthur's assault on the Philippines threatened to cut that femoral artery and starve Japan of the oil it needed to fuel his planes.

Production statistics also fueled more pessimism. Of course, the fog of war meant Japan's military leadership didn't have accurate stats for what U.S. factories and shipyards were producing. Maybe if they had seen how badly they were being outproduced, they would have quit earlier, though probably not.

That said, they didn't need a list of statistics to understand they were getting buried. The graphs below provide some numbers for aircraft and warship production that highlight this industrial mismatch. It wasn't pretty.

Such huge disparities proved decisive and insurmountable for Japan in the Pacific War's battle of attrition.

But wait, there's more!

Japan suffered from a chronic shortage of skilled pilots. When war broke out, it had the best fliers in the world—but two years of heavy fighting had culled their ranks.

However, by 1944, America was churning out a staggering 8,000 new aviators a month, and all of them had completed 18 months of flight school with over 500 hours of flying time. [5]

USN aircrews arrived to combat about as ready for the real thing as you can be from training. In any case, they were far better prepared than their Japanese rivals, who had seen their training pipeline shrink dramatically until they were getting under 100 hours before being sent up into that big meat grinder in the sky.

One Japanese flight instructor lamented the decline in the quality of the instruction new pilots were receiving: "Everything was urgent. We were told to rush men through. We abandoned refinements, just tried to teach them how to fly and shoot. One after another, singly, in twos, and threes, training planes smashed to the ground, gyrated wildly through the air. For long, tedious months, I tried to create fighter pilots. It was a hopeless task. Our resources were too meager, the demand too great." [6]

Navigation skills were phased out or minimized, something essential for operating in the vast expanses of the Pacific. Instead, rookies were advised to stick close to their flight leaders while on missions. [7]

Outnumbered and outclassed in almost every way, by the third year of the war, Japan's airmen were like turkeys to the slaughter anytime they faced off against their American counterparts in the air, who were better trained, more numerous, and flying better aircraft.

This was a fatal trifecta of inferiority for Japanese combat aviation.

But wait, it gets worse still.

Japan also did itself no favors by not having a system to retrieve downed fliers. Thousands were lost when they bailed out over the ocean and no one came to get them. And unless he was fortunate enough to be rescued by a passing friendly vessel, that was it. Being shot down once quite often ended the pilot's flying career.

It was different on the American side, where a very robust search and rescue system operated. Downed aircrews had a decent shot of getting plucked out of the sea and put back into the cockpit of a brand-new, factory-fresh Grumman Hellcat. Meanwhile, their Japanese counterparts were getting eaten by sharks or dying of exposure. [8]

Another systemic difference that distinguished pilot quality was that the U.S. rotated its experienced airmen out of combat after a certain number of missions. They were reassigned back to the U.S. as instructors in flight schools, adding their current experiences and lessons learned to the curriculum.

On the other hand, Japanese pilots flew until they perished, either lost at sea or shot to pieces in their lightly armored flying deathtraps. Even the best pilot's luck would eventually run out, sooner or later, by going up day after day, overwhelmed and facing skilled Navy airmen flying superior aircraft. It was only a matter of time, which is why so few Japanese aces survived the war.

This trifecta of inferiority reached a breaking point during the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944. Here, we see the first of several combat demonstrations of Japan's tactical incompetence that spurred Onishi's decision to adopt his radical change in tactics.

The End of Japanese Carrier Aviation

Outnumbered 2:1 on the eve of the fight, the IJN fleet commander, Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, faced long odds in his mission to prevent the American capture of the Mariana Islands. Fifteen U.S. carriers with 956 aircraft squared off against nine Japanese carriers and 473 aircraft. [9]

Both sides also deployed an accompanying assortment of other warships, including destroyers, cruisers, and battleships, but let's face it, those no longer mattered as much. This was a battle that carriers and planes would decide.

(Though, as an aside, I might add submarines...the U.S. had a small but badass submarine corps that wreaked havoc on Japan's navy and merchant marine...but that's another story.)

Despite the odds, Ozawa had to take a shot. The stakes were too high not to. The loss of the Mariana Islands would put the mainland within range of American heavy bombers. If that happened, the war would come home in a terrible way, much like it had in Nazi Germany, and all the propaganda in the world wouldn't be able to explain away the fact that Japan was losing and its government couldn't protect it.

When the two navies clashed, it lasted just two days (19-20 June) and was an absolute massacre for the Japanese.

Keeping in mind that trifecta of inferiority described above, here's what that looked like in combat:

On the morning of the 19th, Ozawa launched 69 aircraft against the American carriers. None got through the swarm of Hellcats that met them. Only 24 returned after hitting nothing.

Ozawa's second strike had 130 aircraft, of which 98 were shot down after again inflicting almost no damage. While this was going on, the submarine USS Albacore torpedoed Japan's newest and largest fleet carrier, the Taiho, sinking it.

Ozawa didn't give up and sent a third wave of 47 aircraft. These never even located the American fleet. However, they did find Hellcats. Only 7 made it back. [10]

Nevertheless, Ozawa persisted.

He dispatched a fourth and final attack of 82 aircraft from his remaining carriers. Only 28, most of them badly damaged, returned after hitting nothing. Ozawa's awful day wasn't over.

Another carrier, the Shokaku, a veteran of Pearl Harbor and Midway, was sunk by another submarine, the USS Cavalla (like I said, badasses). In a single, calamitous day, the IJN lost hundreds of planes and several carriers while doing no significant damage in return. [11]

The American counterattack, when it came, was punishing. Late in the afternoon of the 19th, Task Force 58's tactical commander, Admiral Marc Mitscher, launched 216 planes from ten of his carriers. When they located the Ozawa's fleet, they sank the carrier Hiyo and damaged the Zuikaku and many other ships. They also shot down another 65 defenders at the cost of 20 of their own. [12]

Navy fliers dubbed this day's slaughter the 'Great Mariana Turkey Shoot' for the disproportionate losses in the air. By the time it was over a day later, Japan was down three more carriers, 410 carrier planes, 200 land-based planes, and most of its aircrews, compared to 123 lost on the American side. It is worth noting since it highlights a point I made above about pilot rescue: About 80 of those 123 losses were not from combat but occurred when they ran out of fuel and had to ditch in the sea during frantic attempts to do carrier landings at night. [13]

However, 59 of those 80 pilots who ditched were rescued and soon back in the fight. Replacing these losses was no problem given America's stockpile of reserve planes by 1944, while Japan's losses were final for both pilot and aircraft, who became sacrifices to Neptune.

Defeated, Ozawa fled north and gave up the defense of the Marianas. Fortunately for Ozawa, Mitscher didn't pursue his beaten foe.

In any case, the battle marked the end of conventional Japanese naval aviation as a viable threat. It never recovered. A defeat like this so close to home had dire consequences.

The loss of the Marianas - of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian - was a crushing blow because it opened the home islands of Kyushu, Hokkaido, and Honshu to area bombing, something the Americans wasted no time in getting started. As soon as General Curtis LeMay took over in January 1945, a ruthless, low-altitude firebombing campaign began that continued until the war's atomic finale.

The battle demonstrated the capability gap between the Japanese and American air forces.

It was only going to get worse.

But first, the road to kamikaze had one more stop.

More Defeat: the Formosa Air Battle (12-16 October) & Leyte Gulf (22-26 October)

October 1944 proved another disastrous month for Japan's fortunes. America’s next target in its Pacific offensive was to weaken Japan’s ability to wage war. Recapturing the Philippines would accomplish that by cutting Japan off from its primary source of oil in the East Indies.

The campaign began in early October when Mitscher's carrier battle groups attacked the airfields on Formosa to degrade Japanese air power in the region. What happened next will sound familiar as the trifecta of inferiority made another appearance over the skies of Formosa. This time, USN fliers went up against the Japanese Army air forces.

Vice Admiral Fukudome, the commander of the 6th Air Base on Formosa, sent up 250 of his fighters to intercept the initial wave of American attackers. Observing from the ground, it looked like they were winning.

As the two sides battled in the distance like two swarms of angry hornets, first one plane fell, spiraling down, and then another, and another. Over the next few minutes, as the aerial combat raged, it started raining planes.

Believing these were American planes falling from the sky, Fukudome clapped his hands and exclaimed, "Well done! Well done! A tremendous success." Only one problem: most of them were his own. He lost about a third of his best interceptors in this initial air battle over Formosa. The remainder perished in the second attack. By the last wave, Fukudome had no aircraft left to send up. It had been another slaughter, more like killer bees versus murder hornets, than two modern air forces slugging it out on equal terms. USN losses were minimal. [14]

Once the Navy had neutralized Japanese land-based air power on Formosa, MacArthur began landing on the eastern shore of Leyte on 20 October 1944. This couldn't go unchallenged, so the IJN made one last desperate sortie to save the Philippines. It was doomed from the start. They didn't have the strength left at this point to have any real shot at victory.

But they tried, oh how they tried. There was little choice but to attack if they didn't want to lose access to that East Indies oil. The balance of forces this time was worse than before. Whereas the IJN had been outnumbered 2:1 at the Philippine Sea, now the odds were over 4:1.

Seventeen U.S. carriers confronted four Japanese, and those were mostly without aircraft. They were to play no role in the coming contest other than serving as sacrificial decoys to lure the Third Fleet north away from the landing zones so Admiral Kurita's surface fleet of battleships and cruisers might sneak in and destroy them.

The Birth of Kamikaze (19-26 October)

This was the situation on the eve of the Battle of Leyte Gulf (19 October 1944) when Onishi sat his staff officers down to brief them. The mood was somber. Everyone knew how bad it was—the last six months had seen catastrophic losses. They had all lived through that nightmare. No one predicted the coming battle would go any better.

Onishi told his audience how the Imperial General Headquarters had authorized an ambitious counterattack against the Americans, Operation Sho (“Victory”), in which the remnants of the IJN would force a decisive battle that might hopefully repel the invaders. This plan had little chance of success, but duty required that they try.

The First Air Fleet's mission was to "provide land-based air cover for Admiral Kurita's advance and ensure that enemy air attacks do not impede his progress towards Leyte Gulf." [15] Everyone in the room knew that was impossible, not with the pitiful inventory they had at their disposal and certainly not after the recent mauling they had received in the air.

Even if they had enough aircraft available - and they didn't - the Americans would just swat them out of the sky as before. What was the point? Duty, of course. If Onishi had ordered an attack, whether with thirty planes or three, that’s what his pilots would have done, no matter if it was going to mean a near-certain death that accomplished nothing. As we've seen, that's what conventional air operations had become for Japanese fliers: virtual suicide missions.

Onishi was also aware of this and had given it a lot of thought. He had an idea. If death were the likely outcome of any conventional operation, what if there was a way to make it count for something?

What if...he wondered aloud, at the cost of one life and one plane, some real damage could be inflicted on the enemy? This would be a glorious death filled with meaning and honor, a hero's end. Even better, it would give the Japanese a way of striking back at the Americans, a capability they now lacked.

Pausing, Onishi glanced around the room at his men before continuing.

"In my opinion, there is only one way of assuring that our meager strength will be effective to a maximum degree. We must organize suicide attack units composed of Zero fighters armed with 250-kilogram bombs, with each plane to crash into a carrier. What do you think?" [16]

The room was silent for several seconds. Onishi let his words sink in. Then everyone started talking at once. It was as if the cloud of collective despair had lifted. His proposal was met with enthusiasm. There was a way forward! No one objected, and the meeting shifted to a discussion about the institutionalization of suicide tactics.

The Logic of Kamikaze

The possibilities were intriguing. In a conventional attack, only the bomb or torpedo might hit the ship. That is…if the aircraft got through the fighter screen and antiaircraft fire. At that point in the war, most Japanese planes weren't. The success rate of conventional attacks was dismally low by the autumn of 1944, making them all but suicide missions anyway, albeit unintentional ones.

And say a plane succeeded in dropping its ordinance, it still had to run the gauntlet of fire in reverse to make it back home. Few did. And if they did, they could expect to do it all over again in the near future. And so on, until their luck ran out, and they were feeding the sharks. All this amounted to an unsustainable attrition with nothing to show for it.

But what if you sent in a suicide pilot loaded with a 250-kilogram bomb, a full tank of combustible aviation fuel, and the aircraft itself to serve as a high-speed, human-guided missile that could close on its victim at 200 MPH and with machine guns a-blazing? This lethal combo would multiply the destructive potential of a solitary attacker many times over compared to a conventional one.

Also, the one-way nature of a suicide mission doubled the range. [17] Most importantly, all this could be accomplished with minimal training and by employing older aircraft, which was all the Japanese had in any case.

Pilots could get a quick crash course (pardon the pun) on kamikaze tactics and some basic flying lessons on taking off and maneuvering before being sent off to their eternal glory. That's all they would need. They weren't looking to reconstitute a corps of seasoned fliers, just single-serving, disposable heroes. They only had to be good enough to hit a ship once. Kamikaze represented a low-cost, minimal-investment solution that worked well within the limitations of Japan's declining warfighting capabilities.

Onishi and his staff concluded that such methods offered the best, perhaps the only, prospect of stemming the Allied tide and saving Japan from defeat.

After the meeting ended, his officers fanned out and pitched the idea to their respective fliers. Would they volunteer for suicide missions against the mighty American fleet? Oh, yes, without a doubt, they would, enthusiastically and almost unanimously. They understood how desperate the situation had become and were willing to trade their lives if there was some remote prospect of turning back the Americans.

The new kamikaze corps started small and was designated Shimpu Tokkotai, or the “Divine Wind Special Attack Force.” [18] However, the alternate vernacular pronunciation was “kamikaze,” and that's the name that stuck. In those first weeks, entire squadrons signed up. Trouble finding volunteers would come later after the most enthusiastic had already killed themselves. But not yet.

Early on, the anecdotal evidence strongly hints that the majority were eager and willing. [19] What's curious about the pilot demographics is that many of the kamikaze "volunteers" came from the universities, specifically the humanities. They wrote poetry, read European literature, and penned long, heartfelt letters to their families before their fatal flights.

The average kamikaze was not the radical zealot one would expect from a suicide pilot. Many struggled to accept the fate they had been assigned but went along out of a sense of duty or under the weight of peer pressure. Others went proudly to their deaths without fear or doubts. Others just went. But most went through with it.

For example, everyone volunteered when Commander Tamai of the 201st Air Group pitched the idea to his 23 pilots. One of them was a fiery young lieutenant named Yukio Seki, aged 23. He was a skilled pilot and a recent graduate of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy's advanced flight school. He had been married for three months to a girl who had sent him a care package. Seki responded, and the correspondence became a long-distance romance. The two met while he was on leave, fell in love, and married. Yet, finding his one true love did not dampen his warrior spirit or make him risk-averse. On the contrary, when he heard about the chance of leading the first wave of kamikazes, he begged his commanders, “You’ve got to let me do it!” [20]

And so they did. Seki had the honor of leading four other Zeros in the first organized kamikaze attack. Before taking off on his last mission, he told war correspondents: “I am doing this for my beloved wife.” [21] This may sound strange to Western ears. People typically don’t volunteer for suicide missions ahead of time, not days after they fall in love and get married. But to the Japanese public, it was a poetic expression of selfless sacrifice filled with deeper meaning.

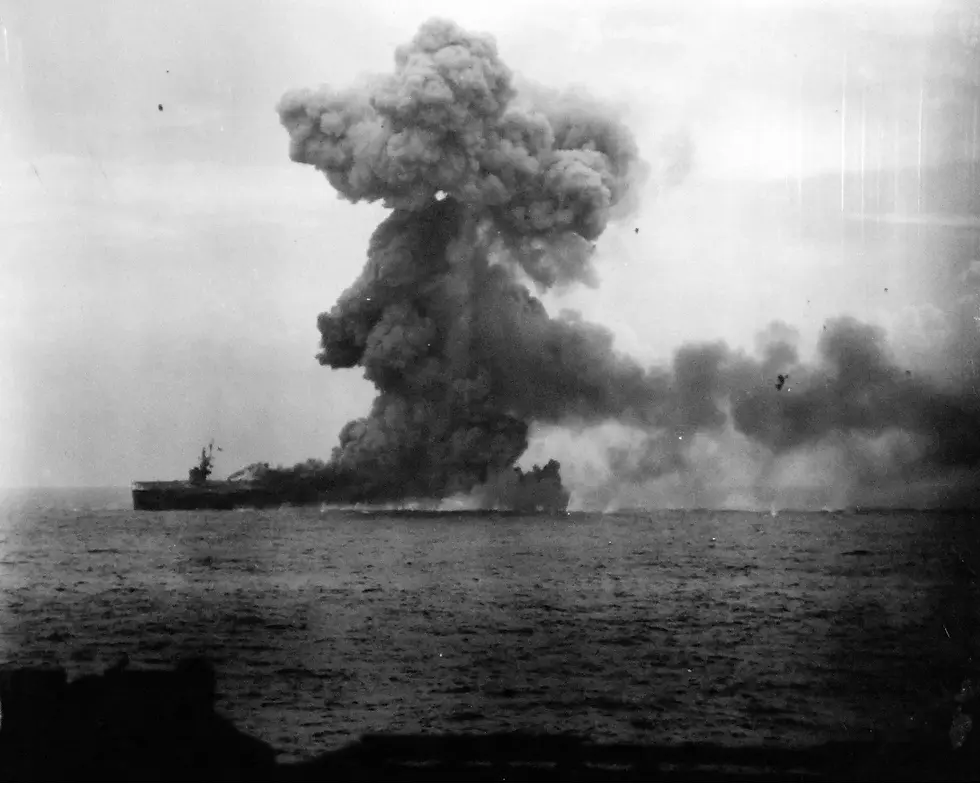

On 25 October, after a few frustrating days searching for targets, Seki’s squadron found Admiral Sprague’s Taffy 1 Escort Carrier Group. Carriers! Exactly what they had been looking for. Seki's Zeros dove out of the clouds and attacked. The first targets were the escort carriers USS Santee and USS Suwanee.

One Zero slammed into the Santee’s wooden flight deck. The momentum from the death dive plunged the aircraft down into the hangar bay, where its bomb exploded and started a raging fire. To make matters worse, a Japanese submarine in the vicinity scored a torpedo hit. Only the heroic efforts of the damage control parties saved the stricken carrier, though it had to retreat to Pearl Harbor for repairs. [22]

Next, the Suwanee took two direct hits. The second did extensive damage to the flight deck when a plane careened into a torpedo bomber that had just landed. The resulting explosion caused a fire that took hours to bring under control. In the end, 107 men died, and another 160 were wounded. The Suwanee survived, too, thanks again to the quick response of its damage control parties. Nevertheless, it had to return to port for repairs.

So far, two carriers had been knocked out of the war at the cost of three planes. Not bad. Not bad at all. This was the kind of success Onishi was hoping for. They weren’t done yet. [23]

The first ship sunk by a kamikaze happened a few minutes later when one of the remaining Zeros nose-dived into the flight deck of the carrier St. Lo. This was quite possibly Seki’s plane, though this is hotly debated.

The bomb this Zero carried blew up in the hangar and started a fire that spread to the ship’s store of bombs and torpedoes, which soon overheated and exploded, setting off a chain of explosions that doomed the ship and took 143 lives.

By the end of the day on 25 October, a modest force of thirteen kamikaze aircraft from the 201st Air Group, including Seki’s five, had knocked out several carriers. Four had been hit (USS Suwanee, USS Santee, USS St. Lo, and the USS Kalinin Bay from Taffy 3 took two hits); one was sunk, and the others were forced to withdraw for extensive repairs. Hundreds of sailors were dead, missing, or wounded.

Despite this lone bright spot, the Battle of Leyte Gulf ended a day later with another resounding victory for the USN. The kamikazes were too little and too late to alter the outcome. Leyte Gulf was to be the last large-scale surface ship battle of the war and finished off what remained of the IJN, which lost another three battleships and four aircraft carriers, in addition to another 29 ships. The U.S. Navy lost just six. [24]

From here until the end of the war, all Japan really had to confront the Americans was a mixture of reliably ineffective conventional air missions, which were in themselves suicidal exercises in futility, and kamikazes, which proved ten times more effective, even though most of them also failed to hit anything.

But for Onishi, this was still a great day. His theory on kamikaze tactics had been tested, and the results were encouraging. He was given the green light to expand the program rapidly. In November, hundreds of new pilots and planes trickled into the Philippines, most of which were assigned to kamikaze units.

One of Onishi’s biggest problems at the start was getting enough planes from Japan to build up his fledgling Special Attack Corps since each mission had (in theory) a 100% fatality rate.

In a testament to the pitiful state of Japanese aviation by late 1944, only half of the initial 150 replacements flown from Japan to the Philippines actually made it. The rest vanished en route, either shot down by predatory Navy patrols or lost at sea. One squadron departed 15 strong; only three made it. [25]

Kamikaze Training and Tactics

Despite this attrition, a truncated suicide training pipeline took shape. Pilots arriving in the theater were given a short introduction to kamikaze tactics that involved a mixture of classroom and flying drills, just enough to get them off the ground and maneuver into a warship. They were taught target identification and rudimentary tactics, especially how best to dive into ships.

They didn't need to learn navigation - an experienced escort pilot would lead them to the targets. They didn't need to learn dogfighting either; they only needed to evade the predatory Hellcats long enough to close the distance and hit a ship. They also didn't need to know how to land - these were one-way trips, after all, though they were taught the basics in case they had to abort for mechanical reasons and return to base.

Kamikaze formations generally comprised four to six planes of all types, with one or two escort-observer Zeros responsible for navigating their barely trained comrades to the targets. [26] In those first few months, no more than a couple dozen kamikazes ever attacked at once. That changed later during the Okinawa campaign (April-June 1945). There, the American Navy confronted weekly waves of 150-350 aircraft.

Two attack methods were taught: a low and high-altitude approach.

Low-altitude attacks came in at 20 to 30 feet above the water. Due to the earth’s curvature, Navy radar systems could not detect planes flying near the surface. This helped them avoid detection until they were within a few miles of their targets. Then, they would climb sharply to 2,000 feet and set up a near-vertical death dive into the target. If done right, the circling combat air patrols and antiaircraft guns had minimal response time. [27]

The high-altitude approach had the attackers come in at 25,000 feet or higher. When 40 miles from the targets, they dropped small aluminum strips to confuse radar systems. Whenever the Hellacts moved to engage, a game of cat and mouse began.

The Japanese fighter escorts would break away and try to get the Hellcats' attention. The intent was not to dogfight or shoot down the Americans - there were too many - but to buy the kamikazes time to close the distance, identify, and hit their targets. Kamikazes were advised to dart from cloud to cloud for safety as they approached the fleets. [28]

Pilots were taught to be patient in target selection. Aircraft carriers were preferred because they offered the most bang for the buck, but anything would do if that were all they could find. Once a proper target had been identified, the attacker set up his final run. The optimal final approach was a steep dive, like a dive bomber.

As we saw with Lt. Seki and his squadron, this turned the plane into a high-speed projectile, which, combined with the plane’s bomb and aviation fuel, enormously increased the collision's damage potential. Escort carriers with wooden flight decks were particularly susceptible to a dive-bombing kamikaze. Even if the attacker was being ripped to shreds by AA fire and its pilot shot dead, the momentum of the dive could still plunge it into the ship.

Moreover, suicide pilots were also taught to aim for the ship’s topside deck. The elevator pits on the flight deck were the most vulnerable for carriers. If this were hit, it would either degrade the carrier’s flight operations or, if extremely lucky, the kamikaze would blow up inside the hangar, causing runaway fires and detonating ammunition stores.

Otherwise, if this were impossible, the kamikazes would aim for the carrier’s “brain:” the island superstructure. Hitting this would disable the carrier and kill its senior officers.

Needless to say, the USN was surprised by the shift in tactics and paid for it.

After the war, Admiral Nimitz confessed in a Naval War College lecture on the shock of confronting suicide pilots for the first time: “The war with Japan had been re-enacted in the game room here by so many people and in so many different ways that nothing that happened during the war was a surprise, absolutely nothing except the kamikaze tactics towards the end of the war; we had not visualized those.” [29]

Fortunately for the Americans, these early attacks during the Philippines campaign were as effective as the kamikazes would ever be. The Americans adapted. If they could never stop 100% of the attackers, they got to where they stopped most of them.

The carrier task force groups began stationing their flattops at the center of the fleet, with the battleships, cruisers, and destroyers providing a formidable ring of anti-aircraft fire that the attackers had to penetrate to reach the carriers.

Constant combat air patrols (CAPs) kept the airspace above the fleet covered and were ready to pounce on any suicide planes that approached. Radar-equipped destroyers were placed further out to provide early warning of impending attacks. These also had CAP coverage. CAPs also rotated patrols over Japanese air bases where Hellcats would swoop down and shoot down any planes that tried to take off.

By the end of 1944, after two months of smaller-scale attacks, one carrier (St. Lo) had been sunk, and another seven were damaged. Four destroyers were also lost, and another three damaged. It didn’t matter. MacArthur’s ground forces steadily advanced, and Japan's retreated until the last air units were pulled out in late January 1945 and re-based in Kyushu.

The battle moved north over the next few months, first to Iwo Jima and then to Okinawa. During the Okinawa campaign between April and June 1945, 1,465 kamikazes sank 27 ships and damaged 164, while 4,800 conventional air attacks sank only one and damaged 63 others. About 20% of kamikazes hit their targets, or about ten times the success rate for conventional attacks. [30] This again validated Onishi's utilitarian logic for Japan's kamikaze campaign: it did far more damage to the enemy at far less cost than conventional attacks.

Overall, from Lieutenant Seki's first attack on 25 October 1944 until the end of the war on 14 August 1945, 45 ships were sunk, among them three escort carriers and 14 destroyers. [31] Hundreds of more were damaged. Around 5,000 sailors died, and another 4,800 were injured. However, it took an average of 123 Japanese lives to sink a ship. [32] Only about one in seven kamikazes at least hit something and caused damage. [33]

Yet the American armada was so massive by 1945 (>1000 ships) that these losses, impressive as they were, barely made a dent in its overall combat strength. Notably, only two carriers were sunk after the St. Lo: the USS Ommaney Bay in January 1945 and the USS Bismarck Sea in February 1945. The heaviest losses came from destroyers, which were tragic but not essential to the success of the overall campaigns.

Bottom line: The Navy's countertactics paid off.

In the end, therefore, after all those thousands of lives thrown away, it didn't make a bit of a difference in stopping America's relentless Pacific offensive. They still came with their planes and bombers and warships and atomic bombs.

Final Thoughts: The Logic of Kamikaze?

A few conclusions:

First, on one level, Onishi was correct: kamikaze tactics did give Japan the best way to strike back at the mighty U.S. Navy. The results proved this. Historian Max Hastings sums it up well, "For the sacrifice of a few hundred half-trained pilots, vastly more damage was inflicted upon the U.S. Navy than the Japanese surface fleet had accomplished since Pearl Harbor. "[34]

The logic of kamikaze was that it maximized Japan's fading ability to inflict damage and casualties at a time when nothing else could. Remember, after Leyte Gulf, most of the Imperial Fleet had gone to its eternal rest at the bottom of the Pacific. Conventional air missions were suicidally ineffective, though the Japanese kept trying them.

Only kamikaze offered the tantalizing possibility that Japan could impose enough pain on the Americans to bring them to the negotiating table rather than insisting on unconditional surrender. This was the goal, anyway.

Japan intended to fight to the bitter end on every island, no matter how small, and to include the home islands if necessary. By doing so, they hoped to make the cost unbearable for the Americans.

They offered concrete examples of that cost during the bloody Iwo Jima and Okinawa campaigns in early 1945. Almost 7,000 Marines died capturing tiny Iwo Jima; about 12,500 Marines and G.I.s perished at Okinawa.

Kamikazes had also taken their toll during these two campaigns, and the average sailor feared nothing more than kamikazes swooping out of the clouds and careening toward their ships with suicidal intent.

If conquering two tiny islands like those had cost so much blood and treasure, what would a ground assault on Japan, a country of 75 million people, look like? Carnage for both sides, that's what. The Japanese forces could be counted on to fight to the death, as always, and kamikazes would constantly harass American warships, as always, with the added motivation that they were fighting for their homeland.

But none of this mattered. In truth, Onishi's suicide corps did nothing to slow down the American advance. America still assaulted the Marianas, the Philippines, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. It wouldn’t stop until the final victory was won, no matter the number of casualties or how many Zeros slammed into their ships. America could always get more ships, sailors, pilots, fighters, and bombers. Japan had fewer and fewer of these every day the war went on.

That makes the logic kamikaze look like something else when you zoom out and see the big picture. It was logical only in a narrow tactical sense: it gave Japan a weapon to do more damage and inflict higher casualties.

But strategically, it was a failure. It was based on the fantasy that Japan could somehow change the war’s course and save itself from unconditional surrender. That was never going to happen.

The date for the invasion - aptly named Operation Downfall - was set to begin on 1 November 1945 with an assault on Japan's southernmost island, Kyushu, and continue in the spring of 1946 by assaulting the Tokyo plain on the main island of Honshu. Planners expected heavy casualties and were willing to entertain any alternatives that might persuade their hard-headed opponents to give up.

Yet, make no mistake, if it came to a ground campaign of conquest, that's what it would be.

We now know there were over 9,000 aircraft in reserve for that hypothetical invasion, and almost all of them were to be deployed as kamikazes. [35] Instead of focusing on unattainable aircraft carriers, they would go after troop transports. Best estimates believed they might take out the equivalent of two divisions, or 30,000 men. [36] No doubt they would have sank more ships and killed more Americans while not changing the outcome of the war one bit.

In any event, it didn't come to that. Nothing had convinced Japan's leaders to give up, not the annihilation of its navy, not the destruction of its air force, not the sinking of its merchant marine, not the loss of its strategic islands, nor the burning to the ground of dozens of its cities by Curtis LeMay's B-29s.

Nothing.

The fools at the helm of Japan's collapsing empire kept pretending that there was still some twisted path to peace that kept them in power and Japan whole. It took two atomic bombs to convince them that enough was enough. Only after the destruction of two more cities and the death of another 200,000-plus of his subjects did Emperor Hirohito agree to the Allied terms of unconditional surrender.

And what about Onishi, the "father of kamikaze?" What became of him? Even after Nagasaki, when it should have been clear that the war could not go on, Onishi passionately lobbied every leading figure in the government, including several from the royal family, for a mass expansion of kamikaze to deal with the impending invasion. They just needed to try harder was all, as if that's not what they had been doing all along. He still thought this was the only "honorable" way forward.

His pleas fell on deaf ears. Kamikaze had been tried and had done nothing to stop the Americans, who now had a city-killing super bomb. So what? Onishi would burn it all down rather than accept the dishonor of surrender.

But then he had an abrupt change of heart after the Emperor announced that Japan would indeed surrender.

The Emperor had spoken, and that was that.

He wrote a letter to his men calling on them to accept the Emperor's decision: "To be reckless is only to aid the enemy. You must abide by the spirit of the Emperor's decision with utmost perseverance. Do not forget your rightful pride in being Japanese. You are the treasure of the nation. With all the fervor of spirit of the Special Attackers, strive for the welfare of Japan and for peace throughout the world." [37]

Then he wrote a haiku:

Refreshed

I feel like the clear moon

after a storm.

And then he took a sword and plunged it into his abdomen and killed himself.

It was a fitting end, all things considered.

Supplementary Materials

Endnotes

Ian W. Toll. Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945. W.W. Norton & Company, 2021, p. 198.

Ibid., p. 202.

Ibid., p. 311.

Ibid., p. 312.

James B. Wood. Japanese Military Strategy in the Pacific War: Was Defeat Inevitable? Rowman & Littlefield, 2023, p. 91.

Max Hastings. Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45. Alfred A. Knopf, 2008, p. 165.

Ibid.

Max Hastings. Inferno: The World at War, 1939-1945. Alfred A. Knopf, 2011, p. 547.

Spencer Tucker. World War II at Sea: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2012, p. 597.

James F. Dunnigan and Albert A. Nofi. Victory at Sea: World War II in the Pacific. Quill, 1996, p. 50.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Spencer Tucker. World War II at Sea: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2012, p. 504.

John Toland. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945. Pen & Sword Military, 2014, p. 537.

Thomas Cutler. The Battle of Leyte Gulf, 23-26 October, 1944. Harper Collins, 1994, p. 266.

Toll, p. 200.

Hastings, p. 166.

Toll, p. 201.

Ibid., p. 373.

Hastings, p. 166.

Ibid.

Cutler, pp. 269-270.

David Sears. At War With The Wind: The Epic Struggle With Japan’s World War II Suicide Bombers. Citadel Press, Kindle Edition, p. 176.

Hastings (Inferno), p. 606.

Hastings (Retribution), p. 171.

Toll, p. 274.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Peter Hamsen. Asian Armageddon, 1944-45. Casemate Publishers & Book Distributors, LLC, 2021, p. 101.

Hastings, p. 393.

The United States Strategic Bombing Surveys, p. 70.

Sears, p. 462.

Hastings, p. 171.

Ibid., p. 393.

Toll, p. 652.

Dunnigan and Noofi, p. 71.

Toland, p. 855.

Works Cited

Bergerud, Eric M. Fire in the Sky: The Air War in the South Pacific. Westview Press, 2000.

Cutler, Thomas J. The Battle of Leyte Gulf, 23-26 October, 1944. HarperCollins, 1994.

Dunnigan, James F., and Albert A. Nofi. Victory at Sea: World War II in the Pacific. Quill, 1996.

Feifer, George. The Battle of Okinawa: The Blood and the Bomb. Lyons Press, 2012.

Gilbert, Martin. The Second World War: A Complete History. Rosetta Books, 2014.

Harmsen, Peter. Asian Armageddon, 1944-45. Casemate Publishers & Book Distributors, LLC, 2021.

Hastings, Max. Inferno: The World At War, 1939-1945. Alfred A. Knopf, 2011.

Hastings, Max. Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45. Alfred A. Knopf, 2008.

Hoyt, Edwin P. Japan’s War: The Great Pacific Conflict. Cooper Square Press, 2001.

Mawdsley, Evan. The War for the Seas: A Maritime History of World War II. Yale University Press, 2020.

Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko. Kamikaze Diaries: Reflections of Japanese Student Soldiers. University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Sears, David. At War With The Wind:: The Epic Struggle With Japan’s World War II Suicide Bombers (p. 2). Citadel Press, Kindle Edition.

Thompson, Robert Smith. Empires on the Pacific: World War II and the Struggle for the Mastery of Asia. Basic Books, 2001.

Toland, John. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945. Pen & Sword Military, 2014.

Toll, Ian W. The Conquering Tide: War in the Pacific Islands, 1942-1944. W.W. Norton & Company, 2016.

Toll, Ian W. Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945. W.W. Norton & Company, 2021.

Tucker, Spencer. World War II at Sea: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2012.

The United States Strategic Bombing Surveys - Air University, www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/AUPress/Books/B_0020_SPANGRUD_STRATEGIC_BOMBING_SURVEYS.pdf. Accessed 30 Sept. 2024.

Wood, James B. Japanese Military Strategy in the Pacific War: Was Defeat Inevitable? Rowman & Littlefield, 2023.

“The World War II Databook : The Essential Facts and Figures for All the Combatants : Ellis, John, 1945- : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, London : Aurum Press, 1 Jan. 1993, archive.org/details/worldwariidatabo0000elli/page/242/mode/2up.

------

PDW

30 Sep 24

Bloomington, Il