Debord's The Society of the Spectacle in the Digital Age

- Paul D. Wilke

- Sep 22, 2023

- 12 min read

Updated: Mar 29

Introduction: Guy Debord and the Society of the Spectacle

In his recent book, “A Web of Our Own Making,” Anton Barba-Kay observes that “…we are conscious of the fact that if the internet makes it easier to keep in touch with our community, it also makes it easier to move away, to do without them, and to isolate ourselves in ways that would have otherwise not been possible” (Barba-Kay 93).

Reading Anton Barba-Kay's thought-provoking book reminded me of Guy Debord and his classic "The Society of the Spectacle." He argued something similar to Barba-Kay over five decades ago about screen culture (different in his time but still relevant). Here's the opening salvo from his 1967 book, "The Society of the Spectacle:"

"In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation" (Society of the Spectacle, #1).

A bit more on Debord's spectacles. They're whatever the economic system comes up with to distract us from directly lived experience. Spectacles mediate our relationships, wants, and desires through screens and headphones. The classic example from Debord's time was television, which remains an essential tool of the spectacle.

However, the internet, high-speed connectivity, and portable handheld devices like mobile phones have taken the spectacle to another level that Debord couldn't have foreseen, though he probably wouldn't have been surprised.

In today's spectacleverse, think of constant online entertainment and distractions spent with eyes and ears locked onto electronic images and sounds, all centered around the mediating wall of the screen: i.e., television, video games, streaming video, and social media. To put it in reductively Debordian terms, spectators spectate in spectacles. In addition, spectacles condition passivity. After all, to spectate is merely to watch what you are being shown by someone else.

This state of conditioned passivity is one of Debord's key points. Speaking in today's parlance, we also call this consuming content, giving it the facade of doing something. But there's more to it. Content consumers themselves become commodities to be exploited, letting this happen by locking their attention onto a neverending series of spectacles.

Consider the YouTube rabbit holes people go down, or worse, how one vapid TikTok video seamlessly transitions into another, and another, and another, or how Netflix will graciously load the next episode automatically.

You need do nothing but watch. Just sit back and let it happen. That next video is loading in four...three...two...one. Your eyeballs are paying the culture industry's bills with your attention even if your money is not.

Modern Spectacles are Everywhere

So while internet technologies seem to offer the potential to add to our well-being, the promise hasn't lived up to the hype. Social media is now a place where most people sit quietly alone and watch, only popping in occasionally with the rare update. A small minority do most of the talking. On Twitter (or X), 10% of users account for 80% of the tweets. For anyone who has been on Twitter/X lately, that sounds about right.

Facebook has a dying mall feel to it these days, in contrast to the wild west early years when people posted promiscuously their thoughts and opinions. Not much is going on now. Most of us avoid anything controversial, rightly fearing the consequences of saying something in a public forum that might come back to haunt us. So we check in, lurk, watch videos, and move on.

To live online like this is to exist as spectators in spectacles. This leaves little room for good old-fashioned face-to-face conversation. We don't talk to each other as much anymore; when we do, we tend to cling to the five pillars. The technological devices we center our lives around - mobile phones, laptops, earbuds - don't encourage connection or conversation. The entire system is built for alienation and separation.

As Debord frames it, “The reigning economic system is a vicious circle of isolation. Its technologies are based on isolation, and they contribute to that same isolation. From automobiles to television, the goods that the spectacular system chooses to produce also serve it as weapons for constantly reinforcing the conditions that engender ‘lonely crowds.’ With ever-increasing concreteness the spectacle recreates its own presuppositions.” (Debord SS #28)

Consider the ubiquity of noise-canceling headphones, which remove us mentally and emotionally from our social spaces. In other words, they separate us from each other. Someone with headphones on is saying: "leave me alone, I'm in my own zone." I see this everywhere, from the gym to the grocery store to the park.

Together alone and alone together.

More counter-intuitively, consider the popularity of podcasts, several of which I regularly listen to on my daily commute. Yet I've wondered if podcasts aren't just the spectacle's consolation prize for those of us longing for (but lacking) meaningful conversation in our lives. In truth, podcasts are audio spectacles but spectacles nonetheless. They take an activity we do ourselves in-person - conversation - and replace it with a spectacle equivalent - i.e., someone else's conversation in which we're mere invisible spectators.

And keep in mind a podcast is a performance of a conversation. Both interviewer and interviewee are acutely aware that everything they say is being said on a stage to a vast online audience. This is not a recipe for any authenticity. Why? Because they're all selling you something: a book, a film, an album, a supplement, a lifestyle. Whatever.

Podcasts are just prestigious commodities made to grab and hold our attention. I feel more enlightened after listening to Ezra Klein talk about polarization than I do after watching twenty-five TikTok videos in ten minutes. Yet they're the same thing: spectacles. After all, nothing's free on the internet ("Hit the subscribe button!").

This has consequences.

As Apple CEO Tim Cook put it, “When an online service is free, you’re not the customer. You’re the product.” Or more accurately, your attention is the product. And what is attention but an expression of priorities? How one spends every day’s finite time reveals where those priorities reside. It’s a truth many of us, including me, don’t like to think about too much when we're frittering our time away staring at a screen.

Debord wrote, "The alienation of the spectator, which reinforces the contemplated objects that result from his own unconscious activity, works like this: the more he contemplates, the less he lives; the more he identifies with the dominant images of need, the less he understands his own life and his own desires" (#30).

This is another crucial point Debord is making. We end up identifying with and reinforcing the content we consume. Put another way, more attention-sucking screen time equals less opportunity to cultivate self-awareness and friendships. And it also equals more alienation. A sophisticated science to hijacking our attention has been deployed on web platforms for years. Every major online platform works hard to keep us glued to our screens in a state of what Debord called "alienated consumption."

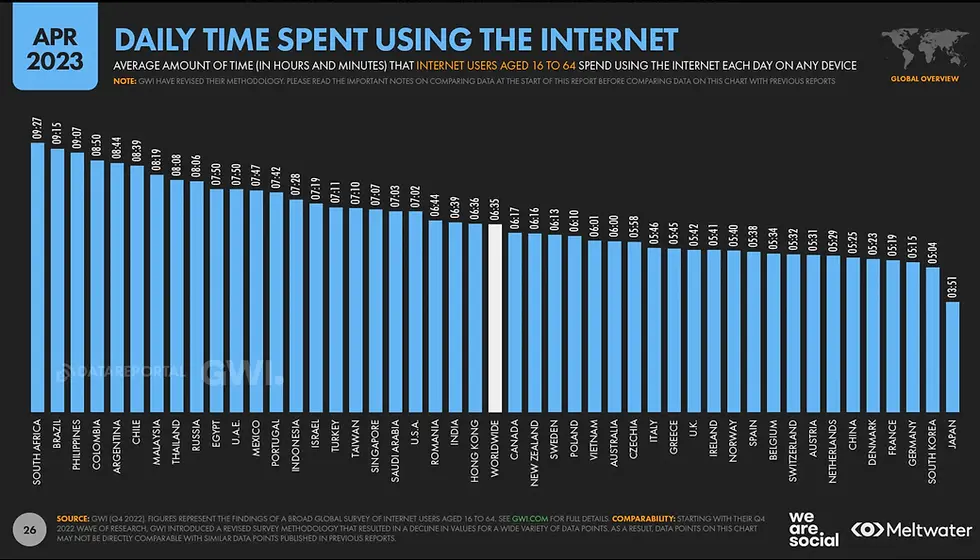

Given that the average person's daily screen time is now about 6.5 hours a day, I'd say they're succeeding. Companies routinely mine our data to feed their algorithms to better give us what we want (or what we think we want) in return for our glazed gazes. They're now training AI to do the same, taking the spectacle's ability to strip us of our agency to another level.

Sooner than we think, intelligent machines will know us better than we know ourselves. They'll even be our friends, if by friend you mean a chirpy worshipper-sycophant who exists to serve your emotional needs, wants, and desires without any pushback, potentially turning us all into middle-class Kardashians. As you might imagine, this does not cultivate deeper forms of intimacy and reflection.

Genuinely healthy relationships don't work that way. For relationships, romantic or otherwise, screens sterilize serendipity. How much intimacy never happened, or will ever happen, or how much love was never made, or never will be made, because Call of Duty or Instagram drugged people into a Lotus-eater lassitude from which they could not be bothered?

No one will ever know.

WFH FTW, SRSLY, STFU! (ROFL)

Next, I want to discuss one other thing that stacks on top of the spectacle's freedom-sapping and alienating superpowers, and that's how technology impoverishes our language. The claim is simple: Limit the range of possible expression and our minds will adapt downward accordingly.

Mediums like the computer and the mobile phone dictate how we communicate. Norms for language used on social media differ from email, which differs from texting, which again differs from video calls like Zoom. Each promotes a specific way of communication that is in many ways inferior to face-to-face interactions.

Email and text are short and quick bursts of functional communication - i.e., just enough to get by. Everyone hates wordy emails or social media posts, so we've trained ourselves not to write them. The goal is quick and to the point before the reader's flittering gaze wanders onto something else.

Even videoconferencing options like Zoom and Teams, crucial during the pandemic, at least for "non-essential" (JK!) white-collar workers, don't offer the nuance and richness of in-person interactions. We become disembodied heads framed in Tic Tac Toe squares. One person talks at a time, and the rest pretend to listen while surreptitiously doing something else, making it another way to fragment our attention.

So much non-verbal communication is lost once we're not in the same space. Reading body language is not possible. Eye contact is removed from the equation. This makes getting the tone right more complicated when we only correspond by text.

Anton Barba-Kay makes the excellent point that electronic means of communication try to make up for these deficits by liberal incorporation of emojis, ALL CAPS, acronyms (LOL, WTF, IDK), and my wife's favorite, the GIF (Barba-Kay 40). It's the only way to make them more expressive. And yet, the fact that we try to approximate real conversation with these shabby substitutes says much about what comes more naturally: conversation.

While technology eliminates space and time - anyone can communicate from anywhere instantaneously - free-flowing conversations are impossible online. You have limited options if you want to express yourself at any length.

You can start a blog (ahem...), but that's a one-way monolog from writer to reader. I'm not trapped in the tiny box of 280 characters or limited to Facebook's etiquette of short and snarky updates with the caloric content of cotton candy. Good for me. My advantage is that I can go on at some length and do so on my own terms.

Still, whatever interactions you and I have, dear anonymous reader, will be limited to a few words in an email you send or a reply in the comments. Minimal. We'll never have any real engagement and sometimes that makes me sad.

I'm playing my own tiny part in the spectacle, it seems.

But if blogging is way too 2006 for you, you can become an influencer on YouTube or TikTok. Or a podcaster. Those are options. Money and celebrity will flow for those few who figure out how to attract enough followers (i.e. spectators) to get rich off of their attention. Everyone else will keep on spectating.

This impoverishment of language combines with the alienating nature of the spectacle to invade the workplace. No space is safe. It always finds new parts of our lives to colonize.

During the pandemic, some thought we were entering a new Golden Age of teleworking. Workers would have less stress, be more productive, and not worry about the daily commute. The pandemic convinced technophiles that teleworking was the answer and that working from home could replace the in-person dynamic of the office. Happy workers could be home alone and professionally productive in privacy while still being part of cohesive teams. But as many businesses and government agencies are finding out, that's not been the case.

Remote workers are atomized ones. Sure, some have thrived; indeed, they love it. The screen is home just as much as the home is home. We're talking about those loners who earn substantial incomes doing mysteriously abstract jobs that defy any easy description ("consultant," "analyst," "project manager," "designer," "developer," et cetera, et cetera, cha-ching). Yet these perfect-fit telework careers are in the minority.

And there's been a cost to all that alone time at home, living like domestic cats with coffee mugs and laptops. Building an efficient team that works well together on projects is more challenging. Productivity doesn't always live up to the hype. Collaboration suffers.

"Zoom fatigue" is a thing people have reported (me too). After all, we evolved to be together, to interpret a whole suite of social queues like body language, eye contact, and facial expressions. On Zoom, eye contact is more difficult. Awkward pauses kill the flow of natural conversation. Plus, staring at yourself on a screen means you're always aware of your appearance, which for many of us, is not a particular source of joy.

If screens mediate the language we use daily, if they offer only limited means of expression, if we only ever string out a few words at a time sprinkled with emojis, then our inner mental worlds will degrade. Our imagination will suffer. Our ability to pay attention will atrophy.

Books won't be read. Romance will wither. Empathy will be frozen out. Emotions will be anesthetized through vicarious experience mediated by screens. The life of the always-online person is that of the sleepwalker, living in a daze and an ever-present haze.

Rich and varied expression takes practice. The spectacle is the enemy of a free-thinking and expressive human being. Our best tool for conveying our thoughts is speech expressed in extended conversations.

The second best expressive tool we have is writing. Talking is easy, but eloquence takes work. Writing is more challenging but leaves something tangible behind. Writing reifies thoughts, turning them into durable things out in the world.

To wrap up my point on the poverty of online means of communication: What if all of our social lives were done in chat rooms? Or by text? Or on Zoom? The thought is appalling. Ten minutes of face-to-face conversation would take hours to do by chat or text. No thanks. I'm talking about a completely different experience with very different possibilities, most of which are far worse at bringing us together.

And, anyway, why wouldn't we want access to the richest, most textured language possible?

Why wouldn't we want to cultivate that face-to-face? Or in a book?

Why would anyone settle for an emoji?

Final Thoughts

This discussion reminds me of Syme, Winston's colleague at the Ministry of Truth in 1984. Syme was an enthusiastic advocate for the reductive aspirations of Newspeak. He explains to Winston how Newspeak's goal was to reduce language by "cutting it to the bone" to "narrow the range of thought." If the words no longer exist as options, the thoughts and concepts they express vanish, creating a simplified language to rule simplified minds.

"It's a beautiful thing, the Destruction of words. Of course the great wastage is in the verbs and adjectives, but there are hundreds of nouns that can be got rid of as well. It isn't only the synonyms; there are also the antonyms. After all, what justification is there for a word, which is simply the opposite of some other word? A word contains its opposite in itself. Take 'good,' for instance. If you have a word like 'good,' what need is there for a word like 'bad'? 'Ungood' will do just as well – better, because it's an exact opposite, which the other is not. Or again, if you want a stronger version of 'good,' what sense is there in having a whole string of vague useless words like 'excellent' and 'splendid' and all the rest of them? 'Plusgood' covers the meaning or 'doubleplusgood' if you want something stronger still. Of course we use those forms already, but in the final version of Newspeak there'll be nothing else. In the end the whole notion of goodness and badness will be covered by only six words – in reality, only one word. Don't you see the beauty of that, Winston" (Orwell 1984)?

Of course, no Big Brother is mandating this reductive culling of our language, yet that's what's happening. Again, the medium determines how we communicate. If a technology only permits short, simplified bursts of language, that's what people will learn to use. If that's what they are conditioned to use, that's how they will be conditioned to think. Syme would understand.

Deeper thinking requires focused attention. Focused attention allows us to tap into more profound insights about existence. Where does one find that in the society of the online spectacle? The spectacles on our little glowing screens aren't made for these deeper, more intimate interactions.

One final thought to ponder: Tech billionaires keep their kids as far as possible from screen technologies. Put another way, they consciously shelter their children from their inventions by sending them to expensive private schools that de-emphasize technology. Moreover, they dramatically limit their kids' use of technology in the home. Instead, they teach them to go outside, make things with their hands, and learn skills with their minds. That's nice. It really is. What a fine example! I'm glad they have the privilege of doing this thanks to the vast wealth they accumulated by keeping the rest of us immersed in spectacles.

Think about that. And when you're done, the pitchforks are stacked in the corner. Help yourself.

Debord gets the last word:

"Imprisoned in a flattened universe bounded by the screen of the spectacle, behind which his own life has been exiled, the spectator's consciousness no longer knows anyone but the fictitious interlocutors who subject him to a one-way monologue about their commodities and the politics of commodities. The spectacle as a whole is his 'mirror sign,' presenting illusory escapes from a universal autism" (SS #218).

Spot on.

Supplementary Materials

Note: I didn't offer much in the way of biographical detail on Debord's life, so I'll remedy just a little bit below. Debord did much more than write this one book. He was the founder of the Situationist Internationale (SI) and the Lettrist International, two avant garde artistic movements that influenced social and political events in 1960s Europe, especially in France. Debord's ideas played an important role in stoking the massive student protests of 1968 as well as the nationwide strike that paralyzed France. Debord committed suicide in 1994 as he was dealing with a deteriorating health situation.

Here are some videos for those interested in learning more about this fascinating man.

Works Cited

Barba-Kay, Antón. A Web of Our Own Making: The Nature of Digital Formation. Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. Bureau of Public Secrets, 2014.

---

Paul D. Wilke

Sep 2023

Falls Church, VA